Fraser Thorne, CEO at Edison Group

According to accepted financial thinking The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) asserts that, at all times, the price of a security reflects all available information about its fundamental value. So current prices are the best approximation of a company’s intrinsic value.

If that is true then why are so many companies being taken over at values of up to 70% more than their stock market price?. What is the market missing? Either accepted economic thinking is wrong or it is suffering from a period of abnormality or maybe something more fundamental is taking place. Something which challenges the hypothesis of existing theories as to how share prices are created.

In recent months FTSE 100 businesses G4S and Royal Sun Alliance (RSA) have both been bid targets with insurer Hastings Group Holdings plc and Urban&Civic plc falling to earlier bid, following other leading industry names such as Macarthy & Stone . Even the doyenne of roadside assistance the AA was finally taken off the market following a 6 year downhill journey.

A common feature is the gulf between the company’s stock price when the bid was launched, and the stock price offered by the potential acquirer. Yet if companies took advantage of the IR resources at their disposal, which have been significantly enhanced as digital capabilities have been developed as a result of COVID-19, this share price gap would have been considerably narrower or the companies might not have been the subject of a bid at all – potentially saving millions in defence fees.

Struggling stock prices have, of course, been a key stock market feature during the pandemic. Like many listed companies, G4S´s stock price fell sharply in the spring and then gradually recovered in the early summer to around 110p – still well short of the 200p at the start of this year – when Gardaworld made its first bid of 145p. Gardaworld’s final bid in December of 235p a share, was not enough to win the competition with Allied Universal trumping them at 245p cash. A 70% premium to G4S’s share price when Gardaworld’s first bid was made. The stock now trades at 257p implying some believe the bidding war may rumble on.

Similarly, Urban&Civic received a bid of 345p from Wellcome Trust, a 64% premium on its trading price at the time, RSA a joint bid from Intact Financial and Tryg, of 685p, a 49% premium and Hastings a 250p bid from Dorset Bidco, a 47% premium.

While the AA bid was at a premium of 40% to its price 4 months prior or 230% from its lows in February. Even serial underperformer Talk Talk was taken over at a 16% premium.

Having reviewed a number of deals over the past six months most had a bid premium of over 40%+ which compares with an average of 15% for the previous two decades.

Takeovers are natural part of corporate development and a key requirement for markets to function efficiently. But their value to shareholders has to be set against the recognition of the underlying value of the business before the bid is made. A premium is normal and is normally required for control but what is most notable is the scale of such premiums. Such price mismatches challenge the foundations of economic thinking, the market is not efficient.

A 10% bid premium is good, 15% very good and anything north of that is exceptional but this depends on the underlying price before the first bid is made. Numbers in excess of 20% suggest the underlying stock is mispriced and therefore the stock market is inefficient. This is hard to fathom in age of open access to so much information but the numbers demonstrate a dislocation between the stock markets value what others are prepared to pay for exactly the same assets.

True, bid prices are not always representative of the value of a business and its future cash flows might improve as a result. But one has to review the fundamentals of stock market valuations when the world’s largest security business can be undervalued by 200%+. Does the market lack the relevant information about the business outlook to make the same assessment as the bidder? Is it that the market is dominated by analysts whose collective glass is half empty? Or maybe it is the risk averse nature of large, bureaucratic investment houses who hope to demonstrate their precise calculations to reassure fund holders that they are looking after their savings.

Some of the quoted discount results from the public/private differential of the cost of capital and the tax treatment of debt v equity. But perhaps a more obvious challenge has to be met by the companies and their boards’ – make sure everyone recognises your value, not just a potential bidder.

With as much investment now funded via debt (PE) as by quoted equity financial theories need a much wider lense. The efficient market hypothesis can only be applied to the market if investors and analysts incorporate the activity of the wider economic and investmsnt market. This must include the valuations applied to private companies. It is a great irony that in the age of the internet he time when more and more information is freely available to all markets are seemingly becoming less efficient.

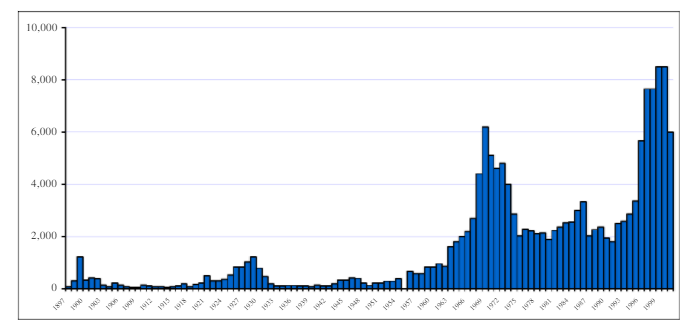

The cost of private v quoted capital plays a part as does the massive growth of private equity v quoted funds, with active money halving in percentage terms in the last 20 years.

EMH theory came to prominence at a time of relative stock market stability, before international takeovers had come into vogue and in a time of greater higher interest rates.

US Mergers since 1897

According to Keynes “markets can remain irrational longer than you can stay solvent” and while they may re balance in the long run they can experience long periods of price dislocation. We are not talking days but months or even years in some extreme cases. Long enough for those closest to the business (the board) to highlight the error and try to rebalance it.

If the stock market cannot see the value opportunity then maybe it is not being given the full picture. When that is the case then it is the obligation of the board to put the market right, yes the business needs to deliver what it promises but the other side of that is to highlight to investors how they will long term returns for shareholders.

While public perception may be that M&A deals and takeovers are decided by thrusting company directors, brave bankers and diligent lawyers, heroically fighting their corners in smoke filled boardrooms.

The reality is that these situations can only arise either when resources are scarce ie a mega merger between two dominate indsurty players scarping over a low growth or shrinking market or if one neglects its duty to achieve a proper value for its shares in the most public of arenas the stock market.

Certainly, the current gulf between share and bid prices suggests that management teams are not doing enough to properly communicate the value of their business to the wide variety of investors, which have holdings in their company.

In these uncertain economic times, clear and direct communication with investors is more important than ever. But not only do management teams need to communicate effectively with their existing investors, reaching out to potentially new investors who are likely to back an existing management team is also important.

A healthy share register is a diverse register incorporating all types of investors from retail through to the large institutions. This means reaching out to a wide and fragmented audience. The modern investment landscape is increasingly characterised by new and exciting pools of capital. The growing significance of these new pools and the value of funds they represent is magnified as a result that active funds have shrunk as a percent of global funds under management by up to 30% in the last 20 years. Boards should focus on building a more diverse and engaged share register, reach out beyond the more mainstream institutional investors to include, family offices, private wealth managers and the end individual investor herself. To ignore this part of the market could be the difference between success and failure in a bid, just ask the board of GKN.

To address these issues, the IR industry has been adopting to a new level of innovation and tech-enabled solutions to respond effectively to these demands. For example, Edison has developed a new market-leading digital approach, which harnesses the latest in data and tech-driven tools, effectively transforming and enhancing the firm’s IR capability to not only efficiently reach out to existing holders but also to target new investors, which in an unwelcome bid situation could make all the difference between independence and redundancy.

Edison’s starting point is to monitor the behaviours of tens of thousands of investors by using smart targeting, with algorithms identifying not just interest but interest with intent to buy. These ‘propensity to purchase signals’ are detected via Edison’s digital content tracking system, InvestorTrack® and layered over market activity and fin depth knowledge of funds flows.

The recent spate of high premium bids highlights management failures to invest in their capital market communications. It is not sufficient to concentrate on the top holders, nor to assume that exhaustive meetings with the sell side is an effective way to get your message carried to the wider market, in the format you want.

Initiating a bid is expensive, even more so defending one. The combined advisory fees alone in the G4s bid are estimated to be in excess close to $30m or close to the annual IR budget of the combined FTSE100. If the FTSE was repriced to close the average bid premium of the last two decades then it could increase in value by more than £300bn.

So, the choice appears straightforward: implement a long-term IR strategy, utilising all the modern digital methods now available to robustly communicate a company’s commercial case and strategy so the business is as fully valued as possible, or neglect this and risk a future bid and if it transpires then spend potentially millions of shareholder funds in fees in a possibly futile attempt to protect the company’s independence. If I was part of a senior management team, I know which option I would choose..